- The Phallus in Pompeii

- The Wings of the Phallus

- The Phallus as a Divine Attribute

- The cult of the Phallus in the following centuries

- Saint Augustine

- Malleus Maleficarum in the Witch Hunt 1482

- Lord Hamilton in 1781

- The horn

- Festa Giapponese del Pene di Ferro, Kanamara Matsuri (Kanamara Festival

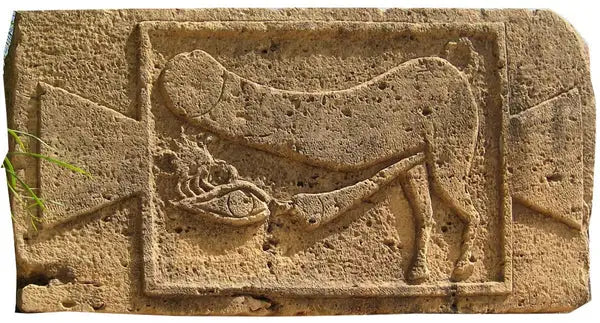

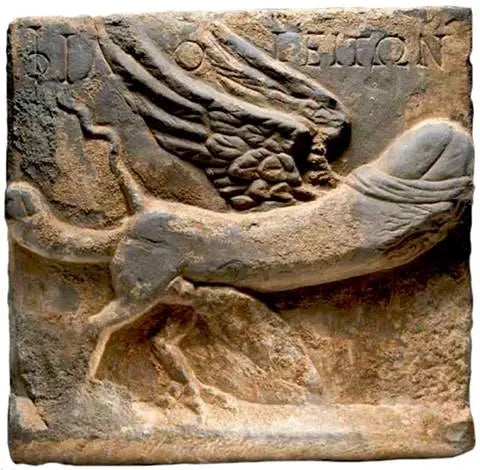

We will begin our journey into the imagination of the Romans with an object that today we would define as obscene, but this term, in the ancient world, did not have the same meaning that it has for us today. A Roman would never have defined obscenus, a winged phallus because in his world, this term indicated what was a bad omen, and therefore the exact opposite of what instead identifies one of the best-known images from Pompeii, from the Roman world and Roman art.

To appeal to all its magical strength, the winged phallus must be reproduced, immeasurable, enormous, propitiatory, capable of driving away evil spirits, capable of giving protection to the house and to work environments, a force of nature against evil, flagellating demons and fascinum: the negative power of the dry eye.

Winged phalluses, twisted phalluses, animal-like phalluses, phalluses that are intertwined with phalluses, phalluses that are grafted onto phalluses. And it truly seems like an endless chase, a real mania, to reproduce this protective symbol on a thousand objects, hanging everywhere.

Religion and superstition are intertwined in a world in which everything seems to revolve around sex which, a source of life and joy, is for the Romans a positive, magical phenomenon, sometimes endowed with a spiritual power that directs life, and, through reproduction, transcends it.

We would define practical superstition or petty magic as that desire to possess an amulet against that oculus malignus, always lurking and codified, in its substance already by Pliny the Elder ; centuries-old source of tribulation for human beings, it must protect the weakest, the most fragile, and this is why, as Varro recounts in De lingua latina, it hangs around children's necks, against the evil eye strong>, a bulla containing a phallic-shaped amulet.

The imagination of Roman craftsmen was often inclined to take flight and the magical power of a symbol can also be seen in the ability to give it haunted or grotesque connotations, wings, in this case.

Also included in the Pompeian road signs, these images, bizarre for us, fluttering here and there, served to chase away the darkest side of our humanity and through a stylistic mutation that will lead to the horn, they continue their work of reclamation even in the contemporary age.

Laura Del Verme

archaeologist

For those who want to know more:

Eva Björklund, Lena Hejll, Luisa Franchi dell'Orto, Stefano De Caro, Eugenio La Rocca (ed.), Reflections of Rome. Roman Empire and Barbarians of the Baltic, exhibition catalog (Milan, AltriMusei a Porta Romana, from 1 March to 1 June 1997), Bretschneider's Herm, 1997.

Megan Cifarelli, Laura Gawlinski (a cura di), What shall I say of clothes? Theoretical and methodological approaches to the study of dress in antiquity, American Institute of Archaeology, 2017.

Carla Conti, Diana Neri, Pierangelo Pancaldi (ed.), Pagans and Christians . Forms and attestations of religiosity of the ancient world in central Emilia, Aspasia edizioni, 2001.

Jacopo Ortalli, Diana Neri (ed.), Divine images. Devotion and divinity in the daily life of the Romans, archaeological evidence from Emilia Romagna, exhibition catalog (Castelfranco Emilia, Civic Museum, from 15 December 2007 to 17 February 2008), All'Insegna del Giglio, 2017.

Adam Parker, Stuart McKie (a cura di), Material approaches to Roman magic. Occult objects and supernatural substances, Oxbow Books, 2018.

Varone, Erotica Pompeiana (Love inscriptions on the walls of Pompeii, Bretschneider's Herm, 2002.

The Wings of the Phallus

The phallus was represented with the but to underline the divine qualities.

As winged, the phallus could ideally connect men with the sky and the otherworldly, offering a connection with the divine.

The wings, and therefore the ability to take flight, they allowed one to abandon the earthly world to access a foreign world, inaccessible and unknown . Since ancient times, the sky has been seen as the home of the divine: from the Olympian gods in the Greek world, to the Christian Paradise.

In the most famous representation of the Christian God, the Creation of Michelangelo, God and Adam are in heaven, lying on the clouds.

Reaching the sky was impossible for most living things on earth, up until just 100 years ago. It is therefore clear how for most of the cultures developed over the centuries, the sky was seen as the place where what could only be imagined resided.

The only ones capable of accessing the sky, this place considered supernatural, were the birds.

The birds, since the Bronze Age, were deemed capable of connection with the divine. The divination of birds was their supposed ability to provide elements for predicting the future. The flight of birds, their appearance in dreams or at particular moments could contain omens and be interpreted for make predictions.

The ability to fly gave birds a special character, otherworldly as it allowed them access to a inaccessible world to all other living beings on earth.

In the Greco-Roman religion, we find the attribute of wings in the God Hermes/Mercury as messenger of the gods, the one who connected the sky with the real world. Cupid, the son of Venus, used his wings to reach humans and make them fall in love by shooting his arrows.

The symbolism of wings extended to Christian iconography, where angels are men equipped with wings, who act as intermediaries between God and humanity. The archangel Gabriel, for example, brought the message of Jesus' birth to Mary. Even the owl, an animal sacred to the goddess Juno, is today a symbol of good luck.

We Today, we have lost that perception of the sky as an unknown, magical, divine, inaccessible place and therefore a place in which to imagine the Gods of Olympus, paradise, the Christian God, the deceased. The expression "he flew to the sky” it is linked to the need to identify a place "other" than the earth, to the daily life of all mortals.

After the invention of the airplanes, this identification of the sky as the seat of the divine is more difficult to understand but remains in some expressions or symbols such as the winged phallus.

In Italian the penis is called "cock", as well as in English “cock”, in American “canary”, in Spanish "cock".

The Phallus as a Divine Attribute

As it is considered the source of life, therefore capable of pro-creating create, has a gift common to the gods, divine.

Precisely to underline its fruitfulness and creative power, an excessive foul is an attribute of Priapus, God of the fields and crops of the Greco-Roman religion.

Phallic representations were placed at the entrances to the fields, both to curry favor with God and to ward off thieves and criminals. The importance of this symbol stemmed from its association with fertility and crop protection, a fundamental concept in an era when agriculture was the basis of society.

In agriculture, as it is strongly conditioned by unpredictable weather events, there was a lot of attention to the effects of good or bad luck. For this reason, the attribute of the God of harvests and harvests assumed a very important role in promoting good harvests. Phallic symbols were a must at the entrances to camps in Roman times. Even today it is common to see enormous horns protecting the countryside, direct descendants of Priapus' phallus.

The cult of the Phallus in the following centuries

Saint Augustine

Saint Augustine (354 AD-430 AD) bishop of Hippo Regis (in modern-day Algeria), recounts these pagan celebrations [1] , describing the ancient fertility processions with a Christian prejudice of strong disapproval:

“Varro says that in Italy certain rites of Liber (Italic god of fertility and fields) were celebrated * ) who were of such unbridled wickedness that the shameful parts of the male were worshiped in his honor at the crossroads. […] In fact, during the days of the Liber festival, this obscene member, placed on a cart, was first exhibited with great honor at the crossroads of the countryside, and then transported to the city itself. […] In this way, it seems, the god Liber was to be propitiated, to ensure the growth of the seeds and to repel the enchantment (fascinatio) of the fields”. [2]

At that time, although considered obscene by Christian clergy, fascinum continued to be used to ward off evil. They were worn as amulets of protection, in particular by children and soldiers (at the time the categories with the highest mortality).

Purinega tie duro (Latin: “Hard to punish”) 1470-1480 (circa). British Museum

Malleus Maleficarum for witch hunts - 1482

In 1484, the Pope officially launched the witch hunt. Hunt that will last two centuries leading to over 60,000 capital punishments, mostly women.

To guide the persecutors, the church commissioned a manual by two Benedictine friars, The Hammer of Witches. A highly successful official manual that the Catholic Church used for two centuries. This witch persecution manual, it contained references to phallic symbolism, highlighting how superstition was still rooted in the popular culture of the time.

The association between bird and phallus is also found in this manual which explains: "finally, what should we think of witches who collect virile members, sometimes even in considerable numbers, even twenty or thirty, and they put them in the birds' nestseating oats or other things as he has been seen to do by many and as is commonly rumored? A man indeed reported that he had lost his member and that it was to recover his integrity He went to a witch. She ordered him to climb a tree and allowed him to take whatever he wanted from a nest in which there were many members. And since he had got his hands on a large one, the witch said to him: "Don't take that !" and added that it belonged to one of the people".

Lord Hamilton letter from Naples - 1781

The ancient cult of the phallus still persisted in Italy at the end of the 18th century. In a letter from Naples, December 31, 1781, William Hamilton describes the custom in Naples among children and women of the working class to wear amulets with phallic symbols, clearly deriving from the cult of Priapus in ancient Rome. The function of these amulets was naturally to protect against spells and the evil eye.

These were amulets in silver, ivory, coral very similar to those found in the excavations of Herculaneum. Hamilton collected many amulets both modern and from the archaeological excavations of Herculaneum to send them to the British Museum.

In the same letter Hamilton testifies to the survival at the end of the 18th century Cult of Priapus in the city of Isernia and its fusion with the Christian cult. During the annual feast of the medical saints Cosimo and Damiano, they came sold in large quantities phallic symbols of various shapes and sizes. These objects had a propitiatory and auspicious function especially for the women who participated in the party, often for remedy their sterility.

Women with flying phalluses, illustration from the Pompeii tourist album, c.1880. Image courtesy of the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction.

The Horn

In Southern Italy and in particular in Naples, thehornhas replaced thephallus as a good luck amulet. The Catholic religion and common morality have led to the disappearance of the phallus as a pagan symbol and lucky charm and to its replacement with the horn. Just as in ancient times farmers placed a large phallus, symbol of the God Priapus, to protect their fields, so even today large horns are inevitable in modern agricultural companies in Southern Italy.

The horn is given as a gift and worn as an amulet to protect against bad luck and the evil eye or from envy, jealousy and malice. It is very widespread and frequent both in Neapolitan homes and in shops and restaurants.

Belief has it that if the horn breaks it means that it has neutralized the evil eye or bad luck, in short it has had an effect.

The Iron Penis Kanamara Matsuri (Kanamara Festival

In Japan, every year in April, the "Iron Penis" festival takes place. Areligious festival that dates back to very ancient times during which processions of chariots with enormous phalli and prayers to propitiate fertility, luck and family harmony.

A slightly macabre curiosity ( * ):

Winged phallus tattoo on preserved human skin, dated 1904-5. From the collection of National Museum of Natural History (MNHN), Paris. Image © MNHN, Paris.( * )

From ancient Greece to Japan, from the cult of Priapus to Neapolitan beliefs, the phallus has been a powerful symbol that has spanned different centuries and cultures. Its meanings, linked to fertility, protection and the connection with the divine, remain imprinted in historical memory as evidence of deep and rooted beliefs.